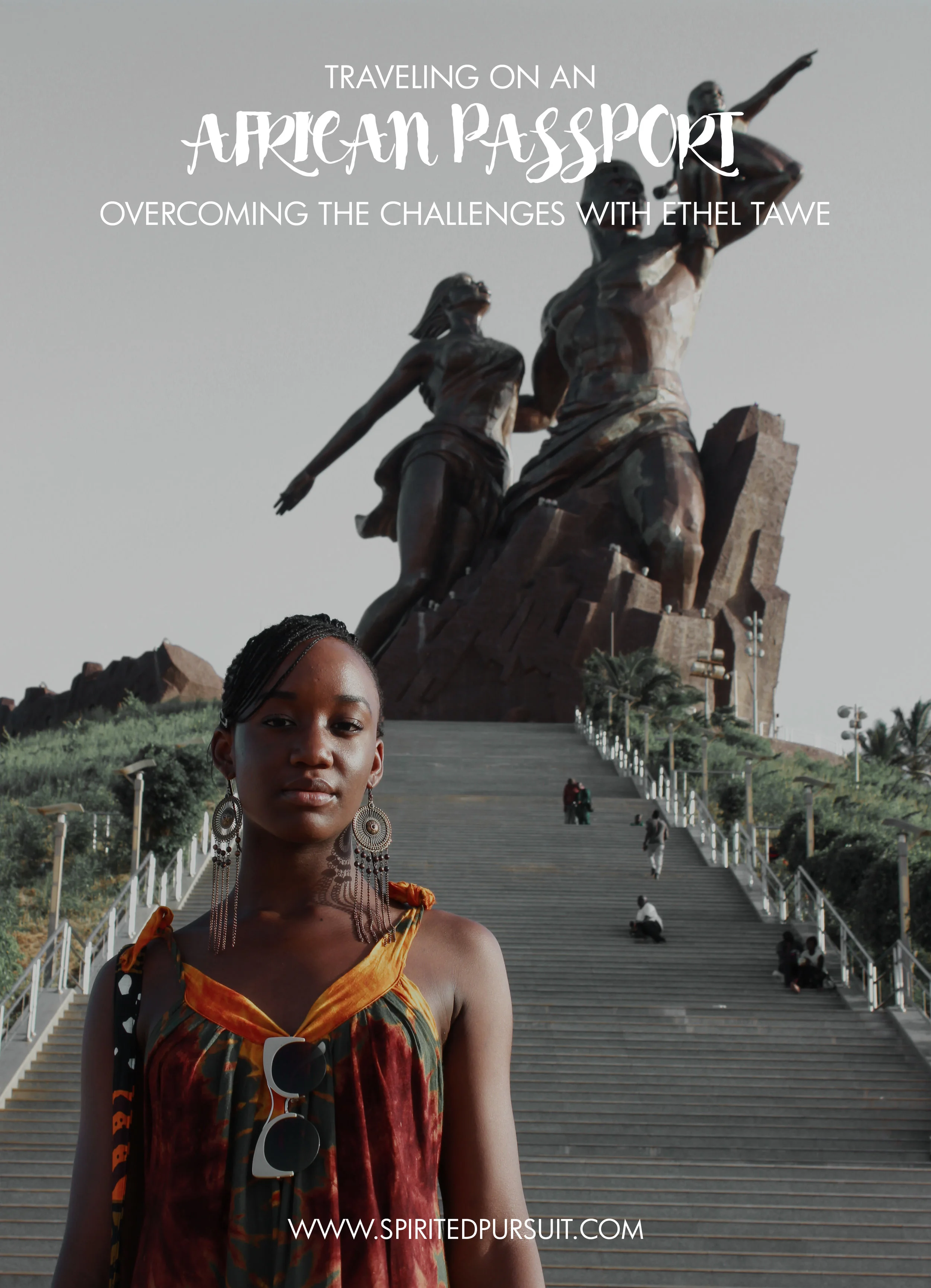

The SP ‘African Passports Series’ is a thread of featured interviews and roundtable stories with select African travel enthusiasts, professionals, and creatives, on their ideas and experiences of travelling within Africa, especially but not exclusively on an African passport. The series seeks to nurture difficult conversations about structural challenges around travel which are not often visible in creative digital spaces. It ultimately aims to provide resources and useful tips on how to navigate challenges with visas, flights, immigration, and general travel as Africans.

Travel is often revered as a personal exploration of interests, new discoveries, and the liberation of rest and leisure. We jet off to Timbuktu in attempt to escape the monotony of routine, for a change of scenery, educational adventures, business, volunteering, or anything in between. However, we must acknowledge that for most people, the process of making these voyages a reality is a luxury in itself — not just monetarily; it can be determined, facilitated or impeded, by what passport you hold. While many in the global north have been arbitrarily saved from the ruthless interrogation of visa and immigration officers, African passport holders know the struggle all too well! As a Cameroonian citizen, this passport inferiority complex was instilled at birth and followed me throughout my travels. Seeking an education in the West became a strange colonial talent show for the visa gods, visiting my family in East Africa was not too much easier, and crossing borders meant reproducing and tailoring different versions of self. Of course, the scrutiny varies depending on the purpose of travel but the stories only change shape. While there has been slow and steady progress in recent years, the long-standing setbacks have been draining and come at major costs.

Guilty Until Proven Innocent. It seems as though the automatic response to African passport holders abroad is one of suspicion or fear. ‘What are you looking for in our land of milk and honey?’ ‘Are you sure you won’t overstay?’ ‘So you’ve had malaria?! What does the rest of your medical record look like?’ While I have never gotten most of these questions outright, there is often an undertone which brews a sense of guilt. The notion of having to repeatedly prove yourself to get bare minimum humane services is a frustrating, baffling, but surprisingly not an outdated experience in this ‘progressive age’. If the pre-travel visa process isn’t dehumanizing enough, you will likely have customs ready to ‘randomly search’ your belongings on arrival.

There’s a Fee for That. While some Africans have it a little easier with governments who’ve negotiated decent bilateral travel agreements, Cameroon passport holders for example still pay hefty reciprocity fees and can only travel to approximately 17 countries visa-free. Due to the frequency of required-visas, many of which are not electronic, we are also more likely to purchase more passport pages in a lifetime. A fee or two or three are included at multiple points of the travel process, depending on your purpose of travel. As a student headed to the UK for my postgraduate studies, I was required to pay nearly double the tuition fee + visa fees + health insurance surcharge + extra costs. If you are to run into any difficulties or need special services, an expediting fee + document assistance fee + passport retention fee or multiple added value services are available to you. Another recent discovery was a fee for contacting immigration regarding any errors or inquiries after receiving the visa. It seems as though perhaps the more money you have, the more answers you get. However, it's even more complicated than that. We, Africans especially, continue to pay for government failures which we are actively distanced from, normalizing this practice under a belief that we ‘have no choice’. As the flow of African returnees accelerates, and as we continue to hone our economic capacity and reclaim space, so should our freedom to explore, exchange, and ‘globalize’ through travel.

For Us by Us? Perhaps Africans should just enjoy traveling within Africa you say? While the creative and cultural renaissance has shone light on new avenues for travel on the continent, our governments are still struggling to agree. How is it that I too, can’t just book a ticket to Timbuktu, Mali (on the African continent), while a European can do so without lengthy questioning. Flexible inter-African travel is surprisingly not a no-brainer, yet high visa fees, restrictions, and suspicion is prevalent within the continent, instead privileging non-Africans. The African Development Bank’s Visa Openness Report 2018 interrogates these dynamics and pressures African countries to reassess their policies. What these structures are founded or maintained on is multilayered, but it is clear that our governments are slowly but surely realizing how much it has hindered our advancement as a people.

The Pan-African Passport. The mere construct of passport systems and the protectionist politics around them have been complicated. The arbitrary nature of African borders themselves, the commodification of our culture, and the polarization of peoples, historically fractured our willingness to seek understanding. Leisure travel is predominantly at the disposal of the ‘transnational class’, while other economic migrants, students, entrepreneurs, and displaced peoples continue to face hurdles in their pursuits. With great anticipation, we now await the introduction of the Pan-African passport as declared by the African Union in 2015; a continental passport that allows free movement within Africa. Despite missing its 2018 roll-out deadline, its potential success would be a game changer on the continent only if all governments choose to corporate. Getting these passports into the hands of the masses is among the major concerns, to avoid it from being exploited as yet another tool for the elite.

Creating Avenues. Despite the challenges, Africans are still traveling— and not just to the Northern Hemisphere. While there have been major push factors such as lack of socio-economic opportunity that lead to desperate mass migration, Africans within the continent are developing our economies, educating, and celebrating ourselves. The change in discourse that removes the West from a pedestal has been facilitated by increased regional integration, and local exchange of ideas and resources. The creative spirit of Africa is cultivating a necessary change and way forward, despite the hurdles of inter-African travel. The system seems to be gradually improving and young Africans are seizing more opportunities across borders.

Patience and Planning. While my African pride runs deep, the bitterness that comes with immigration encounters can be daunting. I have learned to plan ahead, conduct thorough research to avoid disappointment, and consider traveling to the few but growing list of visa-free/visa-on-arrival destinations for my passport type — the Africa Visa Openness Index becomes a very handy and reliable resource for this. Be weary of false information floating around the internet, and call the embassy when unsure. As an artist and academic, my wanderlust magnifies with age, but when recounting my horrible experiences to my mates, some find it hard to belief. While there is an immense increase in exchange of knowledge and experience, African passport holders and others from the global south are still largely excluded. It is a strange concept — we are arbitrarily born into our citizenship and our freedom of movement is then governed, restricted, or monetized by political agreements and disagreements. For now, we must continue reclaiming space by knocking on doors and calling for structural change, even with my green passport and yellow fever card in hand.

So if you hold a hegemonic citizenship, take a second to empathize and consider your passport privilege. Acknowledging your privilege though, should come with a sense of understanding and solidarity with the many who are pushing back against the system. These experiences are not limited to Africa but include much of the global south. Though I still cringe at the thought of visa appointments, I am reminded of the greater terrors of forced migration and displacement. Global political setbacks around these issues are desensitizing us to the nuances of freedom of movement. It is certainly time to revisit many customs around how we travel. Theres a reason why Africa is a ‘trendy’ destination of late, so Africans need to be reciprocated and reap our rightful benefits.

Ethel-Ruth Tawe (b.1994, Yaoundé, Cameroon) is a multidisciplinary artist with a keen interest in engaging dialogue on identity, alternate realities, and diaspora cultures. She holds an MSc in Development Studies from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS, University of London) and a BA in International Human Rights with a minor in Art History & Criticism.

Find her @artofetheltawe on IG